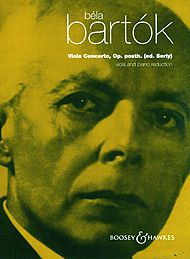

Bartok Viola Concerto

Buy Viola in Music's Collection of

13 famous tunes

Read more

Bartok viola concerto is probably the best known of viola concertos and it is the last work composed by Bartok. We have to thank the great virtuoso violist William Primrose if we can enjoy Bartok's viola concerto. Indeed, Primrose commissioned Bartok to compose it and paid for it. He tells the whole story in his book Walk on the North side, from page 185, if you want to read it all.

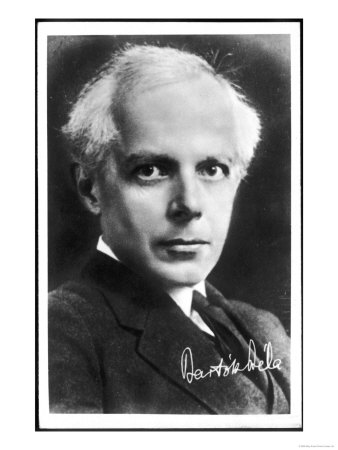

Bartok is now considered one of the main Hungarian composers and you'll find here a short Bartok biography. Bartok was an avid collector and analyst of folk music, especially of Hungarian, Rumanian and Slovak tradition. He even recorded some village music with the first phonographs available. Folk music was his love through all his life and inspired his compositional style.

Bartok's life before the

Viola Concerto

From a very early age Bartok showed a musical talent, encouraged by his parents. He was born on 25th March 1881 and at 11, in 1892, he made his first public appearance as a pianist and after some attempts at the composition of some chamber music works, at 18 he entered the Budapest academy of music to study piano and composition. Soon he attracted attention as a pianist. Later he led the life of a travelling performer and began to develop an interest in peasant music and, after hearing a Transylvanian maid singing, he decided to collect the best Hungarian tunes and write piano accompaniment to make them "art-songs". In 1905 Bartok met Zoltan Kodaly who shared his interest in folk music. They developed a lasting relationship and planned to collect a complete collection of folk songs, seeing the danger that traditional music would otherwise soon be lost. He did several trips to the Eastern parts of the Austro-Hungarian Empire, recording and transcribing peasant songs. Other composers in the past had an interest in folk music, transcribed it and used it in their own music.

What I find particularly interesting about Bartok's activity in this is that he actually recorded village people singing and playing their own traditional music in their villages, during parties or other occasions. I heard some of these original old recordings of violin music and I recognised some of those tunes used by Bartok in his orchestral folk dances.

In folk music Bartok also saw a view to renew his own composition style. In 1909 he started teaching piano at the Budapest Academy, where he remained until 1934. In his compositions Bartok started to integrate more and more folk materials. Folk music was always his love, and he collected and prepared for publication Hungarian, Romanian and also Berber songs from Algeria where he travelled to. He also studied Arabic, Ukrainian and Persian music. This was his main activity for about six years during which Bartok retired from public musical life. This happened from 1912 to the end of the first world war. As Bartok was unfit for military service he and Kodaly were asked to collected folk songs from the soldiers: the songs were later performed in a patriotic concert in 1918 in Vienna. After the war, Bartok re-started his career as a concert pianist and with violinists, promoting also his own works. Later Bartok visited Italy several times and deepened his knowledge of Italian Baroque composers, transcribing and performing their keyboard works.

In 1928 he did his first American concert tour that lasted two months. At that time he also travelled and performed in the Soviet Union and many European countries.

In 1934 Bartok was able to leave the teaching position to work as an ethnomusicologist. At the Academy of Sciences he could complete what he had planned many years before with Kodaly: a full collection of Hungarian folk music. When the collection was finished it included about 14,000 pieces.

When Austria was annexed to Germany by Hitler this affected Bartok, so he changed publisher and started thinking of sending his valuable manuscript to a safe place, worried that also Hungary might be occupied by the Nazis. So he eventually sent them to the USA and later he himself and his family emigrated there in 1940. Bartok spent his final years there, in difficult financial and health conditions, giving some performances, still working on more folk music, teaching and composing. His last works were concertos: one for orchestra, one for violin and our viola concerto.

Origin of Bartok Viola Concerto

As already said, it is thanks to William Primrose if Bartok's viola concerto exists. Indeed, he commissioned Bartok to write it and paid for it.

At that time, in 1945, when Primrose asked Bartok to compose a concerto for him, Bartok was an "obscure composer", as Primrose defines him, at least in the USA and to the big audience, so it was brave of Primrose to ask him to compose a concerto for viola. Most people thought that he had made a mistake in commissioning him a viola concerto. Bartok was having a difficult time in the United States of America, where he had moved during the second world war. Primrose says that Bartok initially wasn't sure about writing a viola concerto, as he didn't know the viola possibilities as a solo instrument well enough. Primrose invited Bartok to listen to a forthcoming performance of him playing Walton's viola concerto. Bartok listened to a radio broadcast of it and then accepted to compose the concerto.

Later they were going to meet to discuss a few things about the concerto, but couldn't meet. Sadly, Bartok died soon after then and the viola concerto was left unfinished. Bartok's friend and composer Tibor Serly undertook the demanding task of putting the pieces together, as the concerto was like a puzzle, written on pages with no numeration, with annotations on many other sheets with other music and a few indications for the orchestration. Primrose also made a few suggestions.

Eventually, Bartok viola concerto was completed and Primrose gave its first performance in 1949 conducted by Antal Dorati.

This version by Tibor Serly was the only one existing, until recently, when new versions of the concerto have been published: one by Nelson Dellamaggiore and Bartok's son, Peter (including the facsimile of the manuscript) and another one by the Hungarian viola player Csaba Erdelyi (2004).

Description of Bartok viola concerto

I've been lucky enough to receive from the very kind and great viola player Michael Kugel a book that he wrote about Bartok viola concerto (and Shostakovich viola sonata). I can't find a better way to describe Bartok's concerto than to refer to his book. I found it wonderful, an eye-opener. Kugel explains very well how Bartok's viola concerto, his last work, contains Bartok's feelings about the situation at that time, his deep and very sad emotions about the world war that had just ended, about his destroyed country. At the same time, Bartok's viola concerto has some happy moments, with Hungarian folk tunes, memories of a happy past.

I recommend to anyone who'd like to know more about Bartok's viola concerto and appreciate it better to read Michael Kugel's book. It is very detailed and has many musical examples but even someone who cannot read music can follow the description of the concerto while listening to it. You can find the book on Michael Kugel's website. Here I'll give you a few hints on the concerto structure, shame I couldn't find a recording by Kugel.

"History of an era - An interpretation of two works for viola"

Shostakovich Sonata for viola and piano and Bartok Concerto for viola and orchestra

"Geschichte einer Ära - Eine Interpratation zweier

Werke für Bratsche"

by Michael Kugel

This is a viola book in two languages, English and German, very useful for viola players as well as music lovers who want to learn about the background of music works.

The concerto is in three movements with no interruptions: Moderato, Andante religioso, Allegro vivace. The whole concerto has a tragic mood, it opens with the solo viola announcing the sad first theme accompanied by some pizzicato chords in the basses; that theme becomes more and more intense and desperate. This first theme is then repeated by the viola in its lower register and taken by the orchestra. The viola tries to play the first theme for a third time, always ending up into something else. Then the music becomes really agitated, with violent chords in the orchestra.

A slower episode with large intervals that sound like a sob, at 8:20 in

the video, at 9:50 the initial theme is here again, then played again in

the very high viola register.

The movement ending is missing in this video, the movement continues in the next one.

First movement played by Yuri Bashmet

At 13:12 the viola starts a Lento (slow), a sort of recitative cadenza that leads to the second movement, with Bartok's indication of Parlando (talking), becoming more and more agitated like a person, with the viola playing like an avalanche of notes from its highest register to the bottom C. The movement is ended by a bassoon.

(click on the titles to listen to samples or on the video for a longer section) The second movement in Serly's edition has the tempo indication Adagio Religioso. It starts like a prayer, melancholic but quite serene, although this atmosphere is interrupted by sobs, Piangendo (weeping) is written in the score, and blows.

Second movement (Bartók-Dellamaggiore revision) played by Hong-Mei Xiao

A short Allegretto episode with harsh chords in the viola leads to the third movement. Maestro Kugel calls it a danse macabre and indeed it is a good definition, as the character of the music suggests the presence of death. The viola plays nearly all the time an aggressive, insistent, chromatic theme in fast notes, restlessly.

Third movement (excerpt) played by Tabea Zimmermann

At some point (1:39 in the above video), however, there is like a memory of happy times, with a folk tune, a simple and serene dance, first introduced by the orchestra and then played by the viola. This episode goes on for a while and then the it becomes moody again.

After a general pause, the viola launches itself into more runs of chromatic fast passages and octave chords, conveying to me a sense of anguish, of not knowing where it is going, repeating fragments from the last movement's initial theme. Then it is the orchestra that starts the last series of fast passages (like an artillery, as Prof. Kugel suggests) before the viola takes its final run, through its whole tonal range to the top of it (as if fleeing) and the music ends there abruptly, like a stroke, sudden death.

Bartok viola concerto recordings

I think that, when listening to Bartok viola concerto (or any other musical work, for that matter), knowing something about the composer as a man and the circumstances surrounding him and his compositions, gives us a different perspective about the meaning of that music.

As a performer, one should acquire this information in order to be able to give this meaning to the music (it's not just a lot of notes) and convey it to the listeners.

So if you want to listen to Bartok viola concerto, apart from my favourite recording of Bartok viola concerto, by Primrose, this CD contains two versions of Bartok viola concerto: one by Serly and one by Dellamaggiore (video of the second movement, above), as well as Serly's own Rhapsody for viola and orchestra.

For more recordings of Bartok concerto, click here

Tips for performers of Bartok viola concerto

For those who wish to study and perhaps perform Bartok viola concerto, can find a good number of useful sources to to help them understand and perform this not, at first, extremely accessible work. The already mentioned book by Prof. Kugel is one but there is also some good advice, from the practical and tecnhical point of view, to be read that comes from no less than William Primrose himself.

Given that Primrose was the one who asked Bartok to compose a concerto for him, that he spoke to him and then was in contact with Serly during the "puzzle reconstruction" phase, that he gave the first and many subsequent perfomances of it (about 150, he says) and given that he was the virtuoso that he was, I think it's well worth reading what advice he can give about its performance.

You can find this useful information, especially about fingerings, in his book Playing the viola - Conversations with William Primrose on pages 115, 118, 141. And he does the same about several other works. Of ocurse it's worth reading the whole book!

I hope the information in this page can help you enjoy Bartok viola concerto more.

Which Version?

Since Bartok's death, the problem of the construction or re-construction of his viola concerto arose among Bartok scholars.

Tibor Serly was the first to undertake the task of putting together the pieces of the composition and his version has been the one considered as the official throughout the 20th century.

However, in 1995 the

manuscript of Bartok's work was published and later a new edition of the

concerto was published by Bela Bartok's son, Peter, edited by Nelson

Dellamaggiore.

After that, a third version has been produced, edited byCsaba Erdélyi, who also recorded it. Here below, in the comments, you can read more details, by maestro Erdélyi himself.

Although most viola players know Bartok's concerto in the first version, nowadays is no longer possibile to ignore these other two versions. Then it is up to performers to decide which one to perform.

Go from Bartok viola concerto to Viola concertos

Tweets by @MonicaCuneViola

Play easily without pain &

nerves

Related pages

Read the book "Stage fright - Causes and cures", by Kato Havas, and play freely

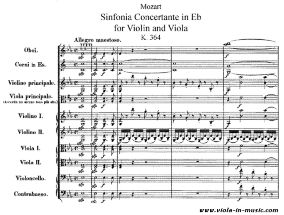

Read the book "Stage fright - Causes and cures", by Kato Havas, and play freelyMozart's

Sinfonia Concertante for violin, viola and orchestra

Antonin Dvorak

played the viola

Buy Viola in Music's Collection of 13 famous tunes (19 pages)

£7.99 and download them instantly

They are in their original keys, so you can play them in sessions with other instruments

Jesu, joy of man's desiring

Michael Turner’s waltz (2 versions)

The

greenwood tree

The south wind

Fanny Power

Ye banks and braes

Skye boat song

My Bonnie

My love is

like a red, red rose

Sportsman’s hornpipe

The road to Lisdoonvarna

Danny Boy (Londonderry Air)

Iron legs

Do you like

Viola in Music?

Support it by buying sheet music here

Download Sheet Music

|

New! Comments

Have your say about what you just read! Leave me a comment in the box below.