Stamitz Viola concerto

you'll love it...

Buy Viola in Music's Collection of

13 famous tunes

Read more

Carl Stamitz viola Concerto in D major is one of the best known (or notorious, for someone) works among viola students and viola players.

I said notorious because many viola players don’t like it. I think this dislike may depend more on other reasons rather than the music itself. Indeed, this viola concerto is very often associated to exams, auditions… not always the most exciting experiences...

I don’t know about you, but I myself realised that most of the things studied at school, I’m not referring to music only, become uninteresting, boring, unbearable, while the same things approached years later, of your own choice, with different people, with different eyes, appear completely new and sometimes I even wonder why I didn’t like them...

Listen to Stamitz Viola concerto while you read

I used to have the same feelings about Stamitz viola concerto, but then I changed point of view and looked at it as a nice and lively piece of music and not as an “exam piece”. I’ve performed it a few times with the orchestra and people in the orchestra and in the audience said they enjoyed it. They didn’t know the concerto so they couldn’t be prejudiced... (or did they only want to be nice to me? I don’t think so...).

Anyway, you can decide yourself, by listening to the videos here.

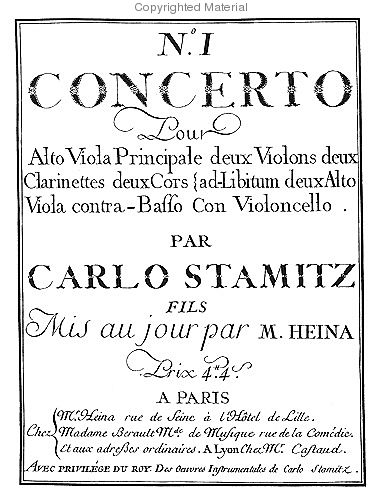

Other than this concerto for viola and orchestra, very few of Stamitz’s chamber, symphonic or concertante works are performed now. The concerto was first published in Frankfurt and Paris probably in 1774, where Stamitz had been living since 1770. It was composed, no doubt, for his own use as a piece to show his virtuosity, through the abundant use of chords, pedal notes, harmonics and even a left-hand pizzicato.

The orchestra

The orchestra is composed of strings, with violas divided playing two separate parts, two clarinets (not commonly used in orchestra at that time but already common in Mannheim) and two horns. Thanks to this writing, the concerto has a rather warmer sonority, maybe with the intent of matching the soloist’s timbre. Sometimes in the second movement the soloist is accompanied only by the two violas.

Stamitz makes an effective use of the different tonal colours of the viola, to suit different musical characters, using all registers of the instrument.

Both in the first and third movement, Stamitz uses chords in different ways: several chords at the beginning of the theme, as a drone accompanying the melody and other times by writing a double melodic line.

The movements

First movement, Allegro

The first movement of Stamitz viola Concerto opens with a long orchestral exposition of the first theme, as you can hear, at first only with strings, building up a crescendo that leads to present the initial theme again, in a more energetic way with the full orchestra. A bridge passage links to the second theme, to conclude the exposition.

Starting with the first theme, the solo viola picks up the musical ideas introduced by the orchestra and develops them with virtuoso passages, including octaves and arpeggios in high positions. Then, an ample modulating bridge leads to the second theme played by the viola soloist. After a short elaboration, the soloist gives space to the full orchestra to play the first theme in A major. A further development, of the second theme with a long passage with arpeggios in many keys, takes us back again to the original key, where some new material is introduced and developed to conclude the movement with soloist and orchestra playing together the second theme.

What I think interesting to highlight in a performance is the way the soloist, while enjoying moments to show off his ability to explore viola possibilities and ranges, at the same time creates in several instances a nice dialogue within the orchestra by playing fragments of the themes with first and second violins in turn, at different octaves.

Second movement, Andante moderato

The second movement is an Andante moderato in D minor, rich in pathos, with a very contrasting mood to the previous and the following movements even though it alternates the minor-key phrases with more serene episodes in major keys. This is a movement where the performer could try to imitate the composer in his performance: the novelist Jean Paul Richter in his novel Hesperus, written in 1795, recreates a concert in which he had heard Stamitz play (the viola d’amore) and, according to him, Stamitz moved the audience to tears.

Third movement, Rondò

The last movement is a very simple and lively Rondò, built more around the alternation between soloist and orchestra, with the solo viola introducing the rondo theme and the orchestra repeating it. After this, all other rondò episodes are performed by the solo viola, with the orchestra accompanying and joining the soloist for the repeat of the A episode. The last episode of the rondo is really a virtuoso conclusion, with a lot of arpeggios and the soloist daringly climbing the, till then, unexplored regions of the fingerboard.

Now, some other details,

a bit more technical

Although Stamitz viola concerto is one of the best-known concertos among violists, in this last movement there are some passages where the interpretation is not quite clear and I myself didn’t find out about this until recently.

Here there are some technical innovations that have gone ignored in modern editions. There are many editions of Stamitz viola concerto, some with a lot of changes done by the editor.

I found two very interesting sources illuminating about this. One is the facsimile of the first two editions of the orchestral parts, published around 1774, with very few differences between them, the other one is Amadeus.

|

Concerto pour alto viola principale, Oeuvre I Deux violons, deux clarinettes, deux cors, deux alto-viola et basse. Francfort sur le Main (s.d. : Ca 1774) - Paris, (s.d. : Ca 1774). Francfort : 8 parties separees. Paris : 8 parties separees. By Carl Stamitz. Edited by Jean Jean Philippe Vasseur. Alto et orchestre. For Viola. Facsimiles. Collection Dominantes. 30 pages. Published by Editions Fuzeau Classique - France (French import). (5397) See more info... |

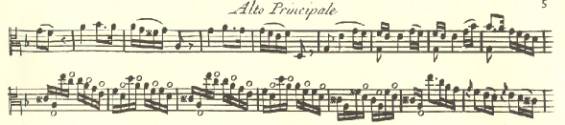

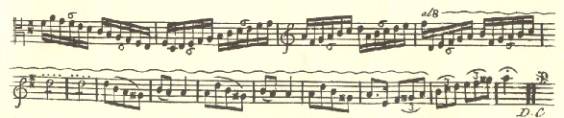

The two editions suggest that, in the Rondo passage from bar 62 to 67, the notes shouldn’t be played normally, as indicated in modern editions. In the facsimile, reproduced below, every other note has a little circle on it, thus the facsimile editor suggests they should be played as harmonics, while Amadeus suggests they should be played with a left-hand pizzicato, referring to other sources to interpret that little circle as an indication for pizzicato. This would be possibly the first example of left-hand pizzicato, and on the viola!

Click on the images below to enlarge them

One of these editions also suggests that the scale in the final episode might go up to the top A, reaching the 11th

position, instead of going down a seventh. In the facsimile, the line

indicating the higher octave stops before the B, whether for musical or

typographical reasons is not clear.

Amadeus’s editor explains that there would be several reasons to sustain this opinion:

- they say the jump of descending seventh (from A to B), instead of a whole ascending scale, was not frequently used

- at that time viola players were more likely to use smaller instruments (cutaway, reduced) than we are used to play nowadays, making it easier to reach high positions on the viola

- it would be a suitable finale for the whole concerto.

Considering Stamitz’s own virtuoso playing style, these suggestions appear to be quite sensible, therefore an enthusiast performer could get into the same spirit and have two extra choices for a performance.

Another interesting thing I noticed by reading the facsimile is that the solo viola plays also the tutti part, and this must have been a very common thing in an era when there were no conductors and the soloist might have led the orchestra from, or with, his section. You can see the same thing in other works of the period, such as Mozart’s Sinfonia Concertante (1779) and Stamitz’s own Sinfonia Concertante for violin, viola and orchestra (1781).

In modern performance (of concertos, not necessarily of Stamitz viola Concerto, it's not performed that often...) this practice is not followed, there is always a conductor (well, nearly always), but it would be a helpful suggestion for a soloist who wished to perform it with a small orchestra and no conductor. How exciting! Soloist and conductor!

I hope this description of Stamitz Viola concerto will help you enjoy it, either you are new to it or know it already.

Buy Stamitz Viola concerto sheet music

If you fancy playing it, buy sheet music and CD

|

Buy downloadable Stamitz viola concerto: printable pdf file with MIDI and Mp3 files

Go back from Stamitz Viola concerto to Carl Stamitz

Viola-in-music.com is recommended by the Encyclopaedia Britannica in its External Links section

Tweets by @MonicaCuneViola

Play easily without pain &

nerves

Related pages

Read the book "Stage fright - Causes and cures", by Kato Havas, and play freely

Read the book "Stage fright - Causes and cures", by Kato Havas, and play freelyBuy Viola in Music's Collection of 13 famous tunes (19 pages)

£7.99 and download them instantly

They are in their original keys, so you can play them in sessions with other instruments

Jesu, joy of man's desiring

Michael Turner’s waltz (2 versions)

The

greenwood tree

The south wind

Fanny Power

Ye banks and braes

Skye boat song

My Bonnie

My love is

like a red, red rose

Sportsman’s hornpipe

The road to Lisdoonvarna

Danny Boy (Londonderry Air)

Iron legs

Do you like

Viola in Music?

Support it by buying sheet music here

Download Sheet Music

|

Alessandro Rolla

virtuoso viola player & composer, one of Paganini's teachers

Berlioz's Treatise on instrumentation and the viola

J.S. Bach's Brandenburg Concerto 3 for 3 violins, 3 violas, 3 cellos

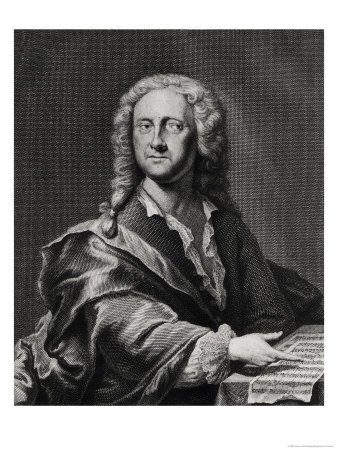

Portrait of Georg Philipp Telemann, composer of the first ever viola concerto

Portrait of Georg Philipp Telemann, composer of the first ever viola concertoGeorg Philipp Telemann's:

first ever viola concerto

J.S. Bach's Brandenburg Concerto 6 for 2 violas and no violins!

New! Comments

Have your say about what you just read! Leave me a comment in the box below.